Inverted Roofs

Lena Henke

Inverted Roofs

Lisbon

Everything we choose in life for its lightness soon reveals its unbearable weight (1), Richard Serra observed when reflecting on the paradoxes of materiality. Describing gravity as both a structuring and fracturing force, Serra’s words articulate an artistic inquiry committed to a tangible reality composed of “constitutive physical elements” (2), a framework that has grounded his work since the late 1960s. In 1968, Serra worked almost exclusively with lead, a medium that demonstrated the ability of abating its own weight and transposing its dense materiality into an insubstantial register. In the seminal work Hand Catching Lead (1968) the artist repeatedly attempts (and mostly fails) to seize falling pieces of lead, demonstrating how gravity constitutes sculpture not merely as a constraint, but as an active “structuring device”.

In dialogue with the lineage of Serra’s early sculptural films (3), Lena Henke’s Inverted Roofs—her second solo exhibition at Galeria Pedro Cera in Lisbon—conjures a world of forms where gravity not only shapes the behavior of matter, but also destabilizes the very conditions of its orientation. Staging a precarious balance between suspension and pressure, Henke’s works seem perpetually at the mercy of weight, or at the risk of overturning and collapsing; a condition ontologically inscribed in the material vocabulary at play. Aluminum asserts a framing solidity, ceramics fracture under their own mass, and watercolors absorb gravity’s pull in the vertical descent of pigment. Yet such somatic quality is not limited to matter alone. The new chromatic palette distances Henke from her previous reliance on darker tones, guiding her works toward a more pastel lexicon that recalls the legacies of impressionist and post-impressionist painting, and their modulation of light across surface (particularly that of Cézanne’s, whose work the artist encountered during her recent residency in the South of France) (4). In each instance, pigment, material and gravity become constitutive elements of inversion, determining how form emerges and destabilizes itself.

Decades later, Serra conceived the site-specific public artwork Gravity (1993). Installed at Washington D.C.’s Hall of Witness (5), a twelve-foot steel slab split the space in two, opening alternate passages while making explicit how spatial experience was constructed through weight and direction. If Serra’s gravity asserts an axis of movement through spatiality, Henke’s exhibition simultaneously amplifies and subverts it, not only by exposing its pressure but, at the same time, by staging an upside-down world that appears to evade it – a home that welcomes us beneath its inverted roof.

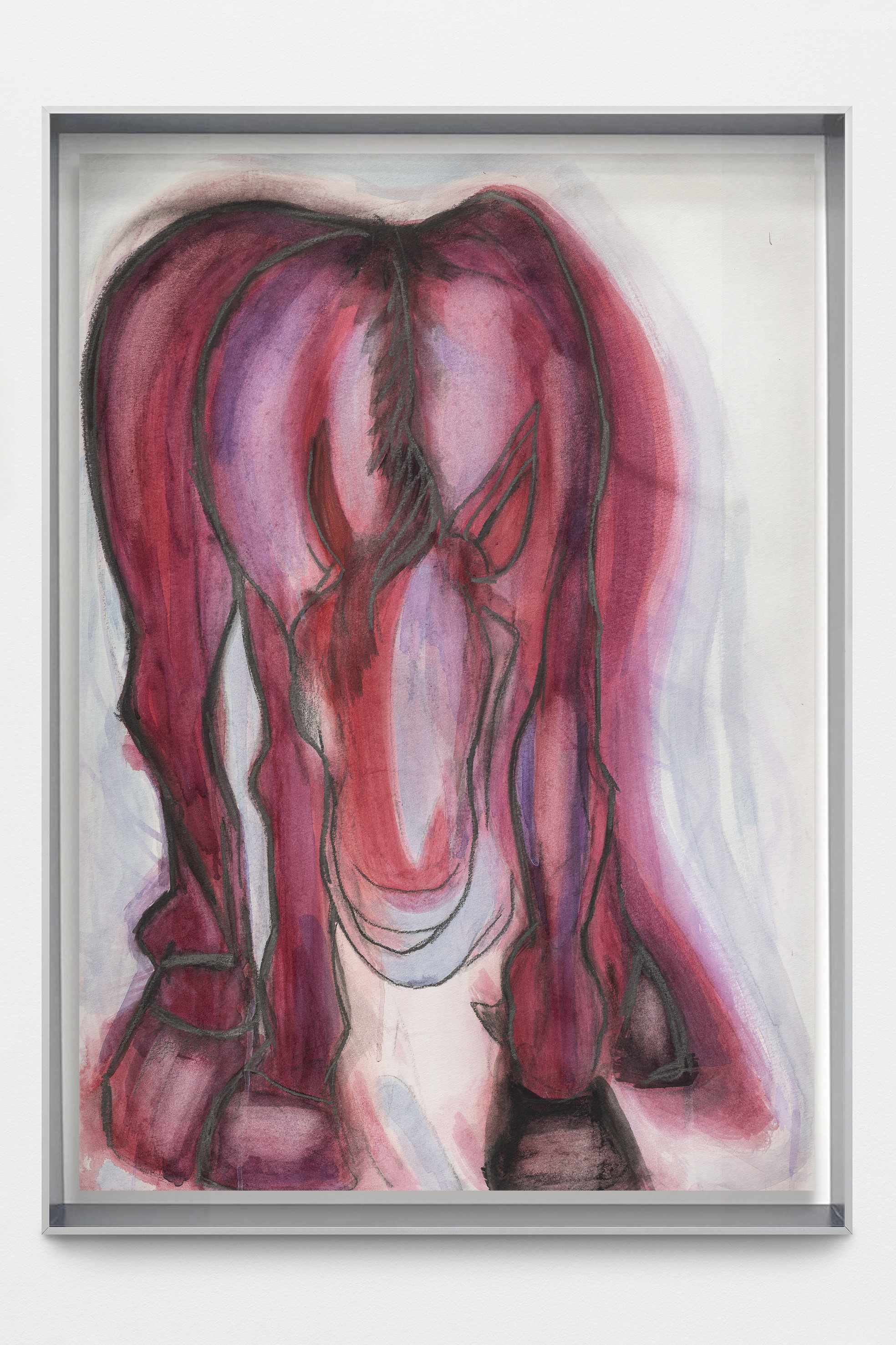

Henke’s ongoing commitment with architectural elements and the domestic (socially encoded sites, shelters to the body and self) is not incidental. From early on, such forms have functioned in her practice as motifs of a conceptual investigation into socio-political narratives and art history, evidencing her interest in the psychology of urban structures through the intervention in public space. In Inverted Roofs, the exterior is re-inscribed into the interior, from the roof tiles mounted upside down, to the large sculptural body that stretches from ceiling to floor, compelling visitors to choose a side. It is therefore significant to see St. Barbara, patron saint of architects, recur in Henke’s recent work. Her face cast into the large aluminum Unforced Error, her body configured into an amorphous, twisted torso ending with a hoof. Human and horse—elements that have accompanied the artist since her formative years in Germany—are merged into the same informe (6) configurations that extend into Henke’s new half-foot, half-hoof sculptures, where inversion also becomes anatomical. Like a butcher’s chart of cuts, her works treat form as fragmentable, subject to disassembly and reassembly.

Henke’s sustained engagement with oppositional structures—of space, matter and categorical distinctions—produces a dialectic condition in which orientation itself is destabilized. One may find resonance with Georg Baselitz’s systematic inversions, where the reversal of pictorial orientation emptied figuration of its narrative legibility, and redirected attention to the work’s construction through line and fracture. In Henke’s new watercolors, reversal operates not only as a formal device, but as an act of subversion that reconfigures perceptual possibility. One thinks of Mondrian’s New York City I (1942), which for decades was hung upside down, now at risk of structural damage were it to be corrected; or Cézanne’s Portrait of Marie Cézanne / Portrait of Madame Cézanne (1866-67), a rare double-sided canvas that consigns one portrait to an inverted position.

In this upturned world, the gravitational logics that pull ceramics to the floor, suspend St. Barbara, or let lead continually escape Serra’s grasp, are the same forces that pressure galleries and render them vulnerable to economic conditions that precipitate closure. In financial terms, the “inverted roof” recalls a stock market chart pattern, coined by Thomas N. Bulkowski in 2005, resembling the bottom half of a diamond and interpreted as a signal of impending recession. Yet in Henke’s universe, this inverted triangle simultaneously transfers into an erotic dialectic, recalling parts of the female body. The latent codes of fetish subcultures are inscribed by the taut pull of ropes that seem to deform Unforced Error, the recurrent trope of the horse as a figure of dominance and submission.

Still, one hopes to resist a purely catastrophic reading. Just as heads remain afloat above tiles, one must sometimes resist gravity’s tight embrace and overturn its logic. As Elizabeth Grosz notes, to be outside is to afford oneself the possibility of a perspective to look (…) inside (7). As such, Henke’s inverted narrative demonstrates that only through the suspension of conventional stability, can new orientations of sculptural and figurative presence be articulated.

—

1. Richard Serra, Writings, Interviews, The University of Chicago Press, 1994: p.185.

2. Miwon Kwon, “One Place after Another: Notes on Site Specificity”, in October, vol. 80, 1997: p.85.

3. A term coined by art historian Benjamin Buchloh in his 2000 essay “Process Sculpture and Film in the work of Richard Serra”, published as a chapter of the book Richard Serra, edited by Hal Foster. Buchloh employed the term to describe Serra’s 16mm films as explorations of sculpture as a process and series of actions, rather than a finished object.

4. Cézanne au Jas de Bouffan at Musée Granet.

5. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

6. L’informe is a concept first introduced by French philosopher Georges Bataille in his “Critical Dictionary”, published in the journal Documents in 1929. Rather than offering a fixed definition, the term suggests what Rosalind Krauss described as “a process of deviance,” capturing the spirit of Bataille’s artistic milieu, in which Surrealism sought to break away from logic and enter the realm of unconscious possibility.

7. Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space, The Mit Press, 2001: p. xiv.